On February 10, 1996, chess player Garry Kasparov began a duel against the Deep Blue machine.

That year, Kasparov was in the prime of his glory. He is the unbeaten world champion since 1985 and will remain so for another 4 years.

For its part, IBM is developing Deep Blue, a 1.4-ton supercomputer designed to play chess.

This machine was incredibly powerful for the time. It is able to calculate between 50 and 100 million potential pledge positions per second and can predict up to 40 forward moves.

To achieve this result, the computer absorbed hundreds of thousands of games played by the greatest masters in history, including Kasparov himself.

The first duel.

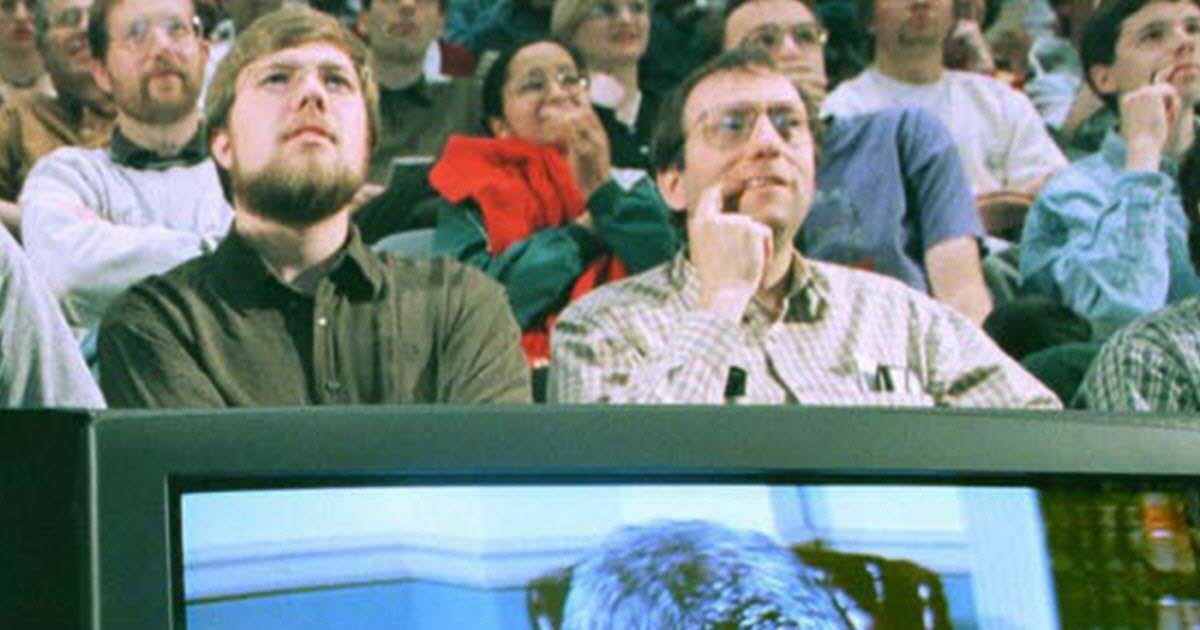

A meeting was organized on February 10, 1996. The stakes are high. It is not just a duel between a man and a computer, but an uphill battle between man and machine.

And the human being who wins it. Kasparov won three matches, two draws and lost one.

revenge.

The following year, on May 11, 1997, a revenge was organized. The player arrives confident. “A computer will not be more powerful than humans,” he tells reporters.

But IBM engineers did a good job. Deeper Blue, its new prototype, and twice the strength of its predecessor.

In the first part, the computer plays a movement that Kasparov does not understand.

Then the hero is destabilized. He doesn’t know if this step is a simple beginner’s mistake or a sign of super intelligent.

He no longer plays to win, but rather to test machine intelligence.

Deeper Blue wins the match with two wins, one loss, and three draws.

Furious Kasparov left the table, an agonizing loser, declaring that the machine would never have won under traditional tournament conditions.

The secret of the winning move.

A few years later, it was discovered that the famously destabilizing blow to the hero was not the result of a strategy, but a simple computer bug.

Among the hundreds of millions of calculated combinations, the machine was not able to decide on one move rather than another, and thus would have played randomly by sacrificing a pawn.

“Certified gamer. Problem solver. Internet enthusiast. Twitter scholar. Infuriatingly humble alcohol geek. Tv guru.”