Cosmic Pac-Man: Astronomers have picked up the first unmistakable gravitational wave signals from the collision of a neutron star with a black hole. LIGO and Virgo detected two such events in January 2020. The smaller neutron star may have been swallowed by the black hole whole and without an accompanying burst of radiation. Evidence for such mixed collisions opens the opportunity to learn more about the origin, evolution and end of these unequal pairs.

Where first guide From gravitational waves in 2016, astronomers recorded more than 50 cosmic collisions with the detectors LIGO and Virgo. Usually two stellar black holes merge, in a few cases they have merged two neutron stars. Also mergers between two extremist partners Unequal audiences They were already there.

But what was missing so far was clear evidence of a mixed binary – a neutron star colliding with a black hole. There was one in April 2019 potential candidates, but the position of the data was too poor to obtain clear evidence. Another event in June 2020 gives riddles Because the second partner was too light for a black hole, but too heavy for a neutron star.

Mixed collisions in a row

Now, for the first time, astronomers have detected clear signals of a neutron star colliding with a black hole. In January 2020, LIGO detectors in the US and Virgo detectors in Italy recorded gravitational waves from this mixed duo twice in a row. “Gravity waves alone do not tell us the structure of the lightest object, but we can determine its maximum mass,” explains Bhooshan Gadre of the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Potsdam.

These analyzes show that the smaller partner in both collisions cannot be a black hole, but rather a neutron star due to its low mass. In the GW200105 event on January 5, 2020, a black hole of mass 8.9 solar masses and a neutron star of mass 1.9 solar masses collided with each other. The energy of this collision released gravitational waves that reached Earth about 900 million years later.

The second event was recorded on January 15th. GW200115 comes from a black hole of 5.7 solar masses and a neutron star of mass 1.5 solar masses, which collided about a billion light-years away.

Is there any associated radiation?

Since the gravitational waves of this second collision reached both the LIGO and Virgo detectors with good quality, the astronomers were at least able to roughly determine the likely location of the event. Using triangulation, they narrowed its position to an area of sky corresponding to the size of about 3,000 full moons.

This approximate location determination allowed other teams to use telescopes to look for the electromagnetic effects of the collision. Such radiation outbursts are often absent when two black holes collide, but they become apparent after neutron star mergers. discoverer. However, it is unclear whether they will also be released in a mixed collision. At least with GW200115 astronomers haven’t found anything.

Swallow whole – like Pac-Man

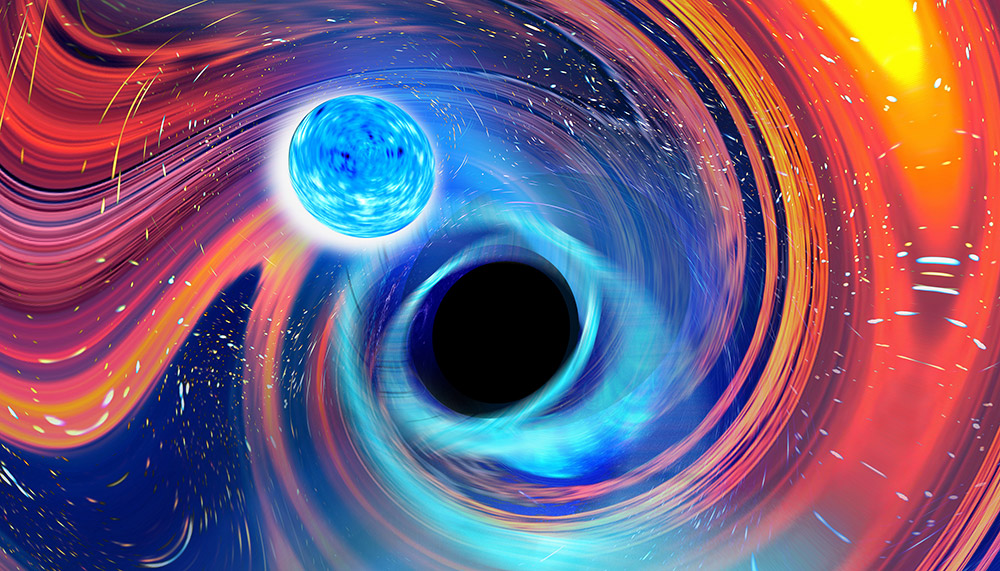

Possible reason: The black hole may have swallowed the neutron star as a whole – leaving no radioactive debris behind. “These weren’t events where black holes gnaw neutron stars first and throw snippets around like a cookie monster,” explains LIGO spokesperson Patrick Brady of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. This ejection would have generated radiation, but we don’t think that happened in those cases.

“In these collisions, two dense, dense objects just don’t come together and unite. It’s more like Pac-Man: the black hole completely devours its partner neutron star,” adds co-author Susan Scott of the Australian National University. These are truly amazing events and we have waited a long time to witness them.”

Many unanswered questions

Events GW200105 and GW200115 clearly show that these asymmetric collisions exist in the universe – and that they can be detected by gravitational waves. At the same time, these collisions open up new opportunities for astronomers to investigate the origin, evolution, and end of these mixed pairs in more detail. “There’s a lot we don’t know about neutron stars and black holes – how small or large they can get, how fast they rotate, and how they are paired,” explains Maya Fischbach of Northwestern University in Evanston.

The LIGO and Virgo teams are currently working on improving their detectors in order to achieve a higher level of sensitivity to trigger the next observation in 2022. As a third member of the group, the Japanese KAGRA detector has also been in operation since 2020. (The Astrophysical Journal Letters, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/c082e)

Cowell: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Northwestern University, CNRS, Australian National University

“Professional food nerd. Internet scholar. Typical bacon buff. Passionate creator.”